The Radiant Sarah-Gabrielle Ryan: Why She's One to Watch at Pacific Northwest Ballet

Hollywood could make a movie about Sarah-Gabrielle Ryan’s big break at Pacific Northwest Ballet.

It was November 2017, and the company was performing Crystal Pite’s film-noir–inspired Plot Point, set to music by Bernard Hermann from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Ryan, then a first-year corps member, originally was understudying the role of another dancer. But when principal Noelani Pantastico was injured in a car accident, Ryan was tapped to take over her role.

Ryan had danced featured roles before, including Maria in Jerome Robbins’ West Side Story Suite. But she had just one day to learn Pite’s choreography. It was a daunting task, but she was determined not to squander her shot. After a session in the studio with Pantastico, Ryan went home and rehearsed for hours in her living room. “I learned the hell out of that role,” she laughs.

Her hard work paid off. When she hurtled onto the stage, draped in a gray trench coat, she stared at the body sprawled on the floor, turned to the audience, her dark eyes opened wide in shock, and let out a horrified scream. The audience was rapt.

Jayme Thornton for Pointe

“The expectation was that we’d throw her onstage and she’d be tentative,” says Pacific Northwest Ballet artistic director Peter Boal. “But she gave a really strong performance.”

Ryan’s success in Plot Point led to a string of featured roles at PNB, from the Sugarplum Fairy in George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker to work by David Dawson and Donald Byrd. But Ryan is no overnight sensation; her success is the result of years of training, discipline and a passion for her art form. That passion also buoyed her during an on-going struggle with body-image issues, and her decision to establish her career a continent away from her close-knit Philadelphia family.

Early Successes—and Struggles

Ryan, now 23, has been dancing since she was 3 years old, when her parents enrolled her in tap, jazz and ballet classes at a local dance studio. At age 5, her teacher recommended she pursue more rigorous ballet training at Philadelphia’s acclaimed Rock School for Dance Education.

Ryan flew up the levels there, and by the age of 12, she’d advanced to the top, the youngest student in her classes. Although she held her own with high-school–aged peers, Ryan knew she was different. “Everyone was older,” she says. “You were expected to look a certain way, but I was still going through puberty!”

That didn’t stop Pennsylvania Ballet, which then did not have an affiliated school, from casting Ryan in its annual Nutcracker. Ryan was 10 when she danced her first role, a toy soldier. Miami City Ballet School director Arantxa Ochoa was a principal dancer with Pennsylvania Ballet at the time, but she noticed the young dancer.

“I just remember her beautiful eyes and big smile,” Ochoa recalls.

Five years later, when Ryan enrolled in Pennsylvania Ballet’s newly revived school, Ochoa was her teacher. “She was that ideal student,” says Ochoa. “Hard worker. Very smart, very talented. To me, she had that thing, that ‘It’ factor.”

Ochoa wasn’t the only one to notice her potential. Ryan continued to win roles in Pennsylvania Ballet productions, including Balanchine’s “Diamonds,” videotaped for PBS. At 16, she was offered a contract with Pennsylvania Ballet’s second company. From the outside, it looked like the culmination of Ryan’s dream.

The reality was less idyllic. Ryan had struggled with body-image issues since her early years at the Rock School; she was particularly self-conscious about the size and shape of her thighs. She remembers one Rock School teacher asking if her Mexican-born mother made good flan. When Ryan replied in the affirmative, he told her she looked like she was enjoying too much of it. Another teacher at the school suggested she go on a liquid diet to drop some weight.

Ryan recalls other “advice,” such as being told not to go out into the sun, so that her skin wouldn’t get too dark. Although she took that particular comment in stride, it compounded her self-consciousness about her appearance. It also strengthened her resolve to work harder in the studio.

At PBII, Ryan was determined to show she had what it takes to succeed as a professional ballerina. But while artistic director Angel Corella told the young dancer that he liked her dancing, she says he advised her to slim down or risk fewer onstage opportunities. She valued his feedback, and her long relationship with Pennsylvania Ballet, but Ryan knew it was time to look for opportunities outside her hometown. She focused her attention on Seattle.

Ryan with company dancers in Jerome Robbins’ West Side Story Suite

Lindsay Thomas, Courtesy PNB

A New Home

Ryan had attended Pacific Northwest Ballet’s summer intensive the summer after joining PBII. She was among 30 young women enrolled in Peter Boal’s class that summer—all excellent dancers, he says—but Ryan stood out.

“She had this kind of go-for-broke presence,” Boal says. “A gutsiness.” He made a mental note. A year later, when Ryan contacted him about an audition, Boal invited her to attend class when the company toured to New York City. At the end of that class, Boal offered Ryan a contract; she joined PNB as an apprentice in the fall of 2016.

“I loved PNB’s rep, I loved the idea of working for Peter,” Ryan says. Although she was scared about moving across the country, she calls it “good scared.”

Ryan in Ronald Hynd’s The Sleeping Beauty

Angela Sterling, Courtesy PNB

Ryan credits Boal with helping to free her from her self-image issues, but that didn’t happen overnight. During her apprentice year, Ryan attended class in “trash bag pants,” concerned that if Boal saw her thighs he’d decide not to cast her. She braced herself for the all-too familiar weight talk.

It never came.

But Boal noticed Ryan’s tension, how she seemed intent on proving herself every time he was teaching class or watching rehearsal. He took her aside and explained that he’d hired her for a reason—he liked her dancing—and advised Ryan simply to dance for her own love of it. By the end of her apprentice year, new contract in hand, Ryan felt she’d found a true ballet home.

Ryan also credits her new-found comfort to the camaraderie she feels at PNB. She gravitated to a small group of Latinx dancers, who reminded her of her close-knit Philadelphia family. Ryan’s mother is Mexican; her father grew up in Belize. The family identifies as Latin American, speaks Spanish at home and celebrates especially their Mexican heritage. Ryan was particularly touched when one colleague, a Seattle-area native, brought her samples of Mexican dishes her own mother had prepared. Small gestures like this helped ease the young dancer’s homesickness.

Ryan had another reason to embrace her new city: Not long after she joined PNB, she caught the eye of a fellow dancer, principal Kyle Davis. They’ve been partners onstage and off for the past three years. “She’s fantastic to work with,” Davis says. “She’s intelligent, open to discussing how steps work and how we can better work together. I personally think that’s a phenomenal quality in a partner.”

Finding Her Voice

During this long pandemic year, Davis and Ryan have had ample opportunity to explore their partnership. They share a Seattle apartment with two miniature Australian shepherds, Hawk and Magpie, who make frequent cameos during the online classes the couple both take and teach.

PNB’s 2020-21 season is all-digital, and when the dancers returned to the studio last August, only those who co-habitated could partner one another. In the company’s opening program, Ryan and Davis reprised the pas de deux from Balanchine’s “Rubies.” While dancing for cameras instead of live audiences hasn’t been ideal, Ryan says she’s learned how to use her face to convey emotions in a more intimate way, instead of playing to the second balcony.

Beyond the pandemic, the past year also ushered in frank national conversations about race and racism, which freed Ryan to speak more openly about her Latin heritage. “It gave me a voice I didn’t always have before,” Ryan says. “I always knew I was different, especially in ballet, but didn’t often talk about it.”

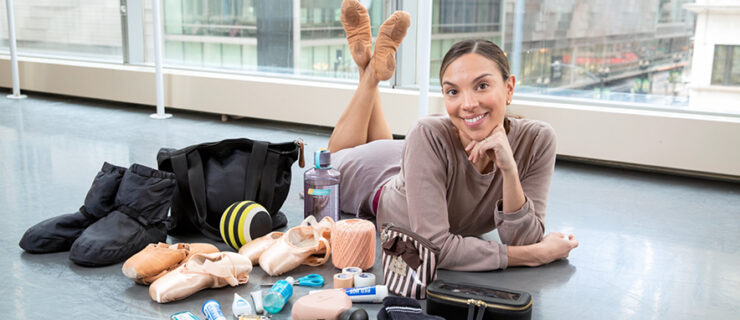

Jayme Thornton for Pointe

Last fall she encouraged PNB to acknowledge Hispanic Heritage Month. But she also wants to see ballet open its ranks to more dancers of color, and to see them advance to the upper echelons of companies like PNB.

Perhaps she’ll be one of those dancers; at 23, she still has a long career ahead of her. Although she dreams of dancing the iconic classical roles—Giselle, Juliet and Kitri—Ryan also looks forward to the contemporary ballets that are a PNB mainstay.

Boal believes she can do whatever she sets her mind to. “Some dancers, there is no ceiling to their capability,” Boal says. “Sarah-Gabrielle Ryan is one of them.”