Raven Wilkinson's Extraordinary Life: An Exclusive Interview

Raven Wilkinson was the first African American woman to dance full-time with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, which she joined in 1955. A gifted artist, she nevertheless faced difficulties while on tour with the company—particularly in the Deep South—because of her race. In 1961 she left Ballet Russe, and a few years later joined the Dutch National Ballet. Wilkinson returned to the United States in 1973, and began performing as a dancer and actress with the New York City Opera—a job she continued until 2011, when the Opera folded.

Pointe spoke with Wilkinson about her extraordinary life.

How did you first come to ballet?

I was so little! My mother took me when I was about 5 to see the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. They did Coppélia, and I remember being so overwhelmed by the orchestra, the curtains, the lights, that I started crying. At that age I was too young for the School of American Ballet, so my mother took me to the Dalcroze school, where I learned tempi and meter and things like that—well, a young person’s version of them. Later, my mother asked me if there were a special ballet teacher I was drawn to. I thought Madame Maria Swoboda was a queen, and I started studying with her. The lessons were a present from my uncle for my ninth birthday, I remember. I was thrilled by ballet. We used to go to the beach in Saybrook, Connecticut each summer, and when the tide would go out, I’d dance on the sandbars.

What was your path to the Ballet Russe?

Eventually Sergei Denham [director of the Ballet Russe] bought the Swoboda school, and it became a Ballet Russe school. He started taking the most talented students into the company. I was considered talented, but I never got in. After my third audition, a friend who worked at the school took me aside and said, “Raven, they can’t afford to take you because of your race.” But I went back for the next audition anyway.

[Ballet Russe dancer] Frederic Franklin gave the audition class. Last year, just before Mr. Franklin passed away, I went to visit him in the hospital. He said to me that the day of that audition, he went to the company staff and said, “You just have to take her—she’s a beautiful dancer.” That was the first time he’d ever told me that.

Mr. Denham took his advice. After the audition, he said to me, “How would you like to be in the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo?” I almost fell over! The next week he asked me to come to his office. He said, “I have a girl in Chicago who I want to give a chance. So you’ll tour with us as far as Chicago, and then we’ll see.” I knew that the itinerary that season took us through the South before we got to Chicago, and realized that he had decided to give me a trial run. So I told him: “I think I understand what you’re trying to say, and I’d rather we spoke about it openly.” He stared at me—not unkindly, but he was definitely surprised—and said, “If I say there’s a girl in Chicago, there’s a girl in Chicago.” [She laughs.] In those days ballet companies were like armies—I was just a little private, and he was the general. You didn’t tell the general what to do!

During that same meeting, I also told Mr. Denham that I didn’t want to put the company in danger, but I also never wanted to deny what I was. If someone questioned me directly, I couldn’t say, “No, I’m not black.” Some of the other dancers suggested that I say I was Spanish. But that’s like telling the world there’s something wrong with what you are.

What happened when you began touring with the company?

For two years, everything went very well. We had many foreign people in Ballet Russe, lots of South American dancers, so most of the time I didn’t have to worry too much; we all looked a little different. I got some nice solos to do, like the Waltz in Les Sylphides.

Then I started to have problems. I remember one time in Montgomery, Alabama, the tour bus rolled into town, and everyone was running around with white robes and hoods on. They stopped traffic, there were so many of them. There was a rapping sound on the bus door, and this man jumped on in his hood and gown. Several big strapping male company dancers got up and moved toward him. He threw a fistful of racist pamphlets all over the bus before they chased him out.

That afternoon, when we got to our hotel in Montgomery, a bunch of us went down to the dining room for dinner. When we walked in, it was full of lovely couples, families with little children—a wonderful family atmosphere. Then, as I pulled out my chair, I realized that they all had Ku Klux Klan robes on the seats next to them. I remember thinking, here are people who can be so cruel and ugly, and yet they’re so loving toward their own families. In a way it made me less frightened of them. They lost some of their power in my eyes.

How did your fellow company members react to things like that?

They were so wonderful. My roommate, Eleanor D’Antuono, was incredibly protective of me. And if it looked like there might be trouble after a show, company boys would appear at the stage door to escort me back to the hotel. They were just elegant in their way of understanding and helping.

Experiences like that are revelatory. But I was lucky. The fact that anybody had an opportunity like mine that many years back, that’s really quite a considerable thing.

How did you end up joining Dutch National Ballet?

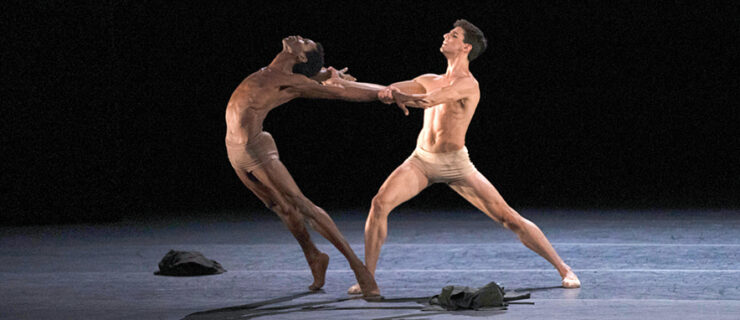

When I left Ballet Russe, I stopped dancing for a while. It wasn’t me running away from dance, though I did feel a little disappointment at the limitations that were placed on my career. But I found that I missed dancing terribly. Eventually my friend Sylvester Campbell, an African American who’d gone to Europe to dance with Dutch National Ballet, came to town. He was just extraordinary, with grand jetés that topped Nureyev’s. He asked me if I’d be interested in coming to Holland—he said, “You should be dancing Giselle!” Eventually I did get a Dutch National contract, and I danced some nice things there. A lot of Balanchine, which I hadn’t done much of until that point, and the Swan Lake pas de trois.

Why did you return to the United States?

I loved Holland, but I missed my own country. I missed the very thing we complain about when we’re here—America’s diversity of philosophy, of feeling, of custom. It makes for a difficult society sometimes, and yet you feel its absence in a place like Holland, where everyone has the same history. So I came home.

Soon after I got back, I walked by Lincoln Center. I remember thinking, Oh, dear, I wish I’d had a chance to dance here. I was nearly 40 and assumed that I never would. Yet the next day I got a call from the ballet master for the New York City Opera, who asked if I could come in and dance in two operas. I’d just stopped taking class—I thought I was retired! But I couldn’t say no. So I went to the New York State Theater and learned the operas, and I ended up enjoying it so much that they found other work for me to do, both dancing and acting parts. I didn’t stop dancing completely until I was 50, and I continued doing acting roles until 2011, when the poor New York City Opera got swallowed up. I told people that I had “organically retired”—the company went out of existence, so nobody had to say, “OK, Raven, it’s time to stop!”

What are your thoughts on ballet’s continuing diversity problem?

My never-ending question is: When are we going to get a Swan Queen of a darker hue? How long can we deny people that position? Do we feel aesthetically we can’t face it? I think until we start seeing it regularly, we’ll never believe it. But I’m sure that won’t take another 60 years to happen.