Ballet Prodigy Li Cunxin Was a Stockbroker Before He Became Queensland Ballet’s Artistic Director

An artistic director’s position was far from Li Cunxin’s mind when the Brisbane-based Queensland Ballet came calling in 2012. Since his retirement from the stage in 1999, the Chinese-Australian dancer had embarked on a highly successful career at the helm of a stockbroking firm. His wife, former dancer and current Queensland ballet mistress Mary McKendry Li, changed his mind, Li remembers. “She said, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice to give something back to the art form that we both have benefited so much from?’ ”

Seven years later, Li’s contribution has been dramatic. Queensland Ballet, once a struggling choreographer-led company, has become one of Australia’s most exciting repertoire ensembles, with Liam Scarlett on board as artistic associate. The budget has more than quadrupled, to over $20 million USD, and Li has launched not one but three major construction projects, with world-class headquarters, a theater and a new academy all in progress.

Li has never been one to play it safe, as his 2003 autobiography, Mao’s Last Dancer (later adapted into a film), made clear. After training in Beijing, he defected as a young dancer in Houston in 1981, and went on to have a highly successful career with Houston Ballet and The Australian Ballet. Still, finance proved his second calling. “I come from such poverty in China, with a large family back there, that as a child my dream was to help them financially,” Li says.

After being an unlucky finalist for the position of artistic director of The Australian Ballet in 2001, Li gave up on the idea of returning to the dance world full-time—”it was too painful”—but maintained other ties, serving on the board of the Melbourne-based company and on the Australian Council for the Arts. Before his predecessor at Queensland Ballet, the French choreographer François Klaus, resigned in 2012, Li was asked by the board to do a peer review on the standard of the company. “The standard wasn’t where I thought it should be,” he says. “The company was defined by François’ work, the dancers weren’t really being challenged, and they were struggling with box office.”

The headhunter looking for the next director didn’t call him, however: He contacted Li’s wife, whose family hails from the Queensland region, to ask if she’d be interested in the job. She declined, but suggested her husband.

After moving from Melbourne to Brisbane, Li embarked on a phase of rebuilding, with significant dancer turnover in order to raise the company’s classical level. “I did auditions in Asia, Europe, North America in my first season,” he says. He shifted the focus to high-quality, more expensive stagings: In Li’s first year, Ben Stevenson’s Cinderella commanded more than double the budget of any previous Queensland Ballet production. “The board was freaking out,” Li says with a smile. “I felt that whatever I bring onstage or offstage, including community workshops, had to be quality, from the costumes to live music.”

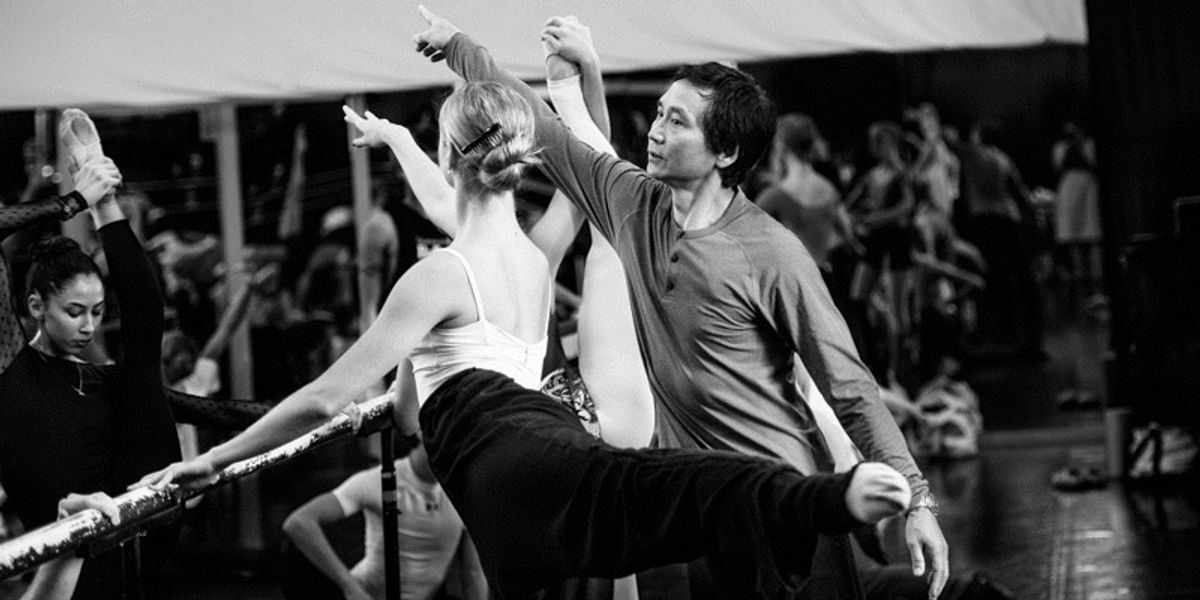

Li Cunxin teaching company class

Ali Cameron, Courtesy Queensland Ballet

But Li had the financial savvy to back up his ambition. “A lot of artists and directors don’t really understand the value of money,” he says. He invested in co-productions, including Scarlett’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Greg Horsman’s staging of La Bayadère (shared with two other companies), and knew how to tap into philanthropy, which is providing the majority of funds for the company’s $42-million USD renovated headquarters, set to open in 2020. Counterintuitively, however, for Li, building a sound financial operation has meant prioritizing artistic goals. “One thing that gets a lot of companies into trouble is that they are very much dictated by the business side, so often they lose the artistic focus,” he says. “People have to be excited by your vision.”

As a result, Queensland Ballet may well be the fastest-growing classical company in the world. From 17 dancers and 6 trainees when Klaus left, Queensland Ballet has expanded to a total of 55 (including 12 Jette Parker Young Artists), scheduled to rise to 60 next year. The number of annual programs has doubled, to six. Li has introduced a steady diet of classics, from an annual Nutcracker to Coppélia, Balanchine ballets and Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet, as well as contemporary ballet works by the likes of Jiří Kylián and—this year—Trey McIntyre.

Li’s biggest coup remains the hiring of the in-demand Scarlett as an artistic associate in 2016. The British choreographer relishes the differences between the smaller Australian company and his alma mater, The Royal Ballet, where he is artist in residence: “It’s so far away from home that it can be almost treated as a second one. They’re a really tight-knit company.” Queensland’s narrative-heavy repertoire has helped the dancers Li hired mature into strong dance actors, and Scarlett fed off their personalities earlier this year to create a striking two-act adaptation of Choderlos de Laclos’ novel Dangerous Liaisons, another co-production (with Texas Ballet Theater).

Li worked behind the scenes to ensure the conditions for Scarlett’s world premiere were right. “Often when you choreograph on a company like The Royal Ballet or the Bolshoi, you don’t get enough time, because other works need to be rehearsed,” says Li. By contrast, Queensland Ballet generally works on one program at a time. “Here, he has undivided attention. Everything is focused on that ballet to make it as good as possible.” With productions like Dangerous Liaisons, Li is on track to realize his goal—fashioning Queensland Ballet into a powerhouse Australian company.

Audition Advice

Queensland Ballet’s season starts in January, and the company holds yearly auditions in Brisbane and Melbourne. “It’s about the quality of the technique,” Li says. “I’m also looking for what kind of focus dancers bring to their work.” Most company members now come from the Jette Parker Young Artists Program, an apprenticeship that provides young dancers with a full salary.

At a Glance

Queensland Ballet

Number of dancers:

43, plus 12 Jette Parker Young Artists

Length of contract:

Year-round (January–December)

Starting salary:

$37,320 USD

Performances per year:

Approximately 115

Website: queenslandballet.com.au