Prince in Waiting: American Ballet Theatre's Joseph Gorak

It’s a beautiful evening in May, but inside the Metropolitan Opera House the atmosphere is hushed and filled with foreboding. As Lensky in American Ballet Theatre’s Onegin, Joseph Gorak enters the darkened stage. It is a pivotal scene. Heartbroken over a flirtation between his fiancée, Olga, and his friend Onegin, he is moments away from a fatal duel, and painfully aware of his own mortality. In a lyrical yet powerful solo, Gorak manages a rare feat: He renders the depth and intensity of Lensky’s pathos without veering into melodrama. And his portrayal proves the perfect foil to principal dancer David Hallberg’s misanthropic Onegin. For a brief moment, the spotlight is all his.

In the last two years, 23-year-old Gorak has emerged as one of ABT’s most promising young dancers. While the company abounds in powerhouse men, Gorak is a different breed. He projects a refined simplicity, and his natural facility and crystalline technique have caught the eye of audiences and critics alike. It would be easy for him to simply rely on his high insteps and polished pirouettes to captivate; naturally talented dancers often wear their gifts like a veil, hiding their vulnerabilities behind technique and physical beauty. Yet Lensky proves that Gorak carries a true artist within him. Like many promising dancers, he has reached a critical career juncture. It remains to be seen whether he’ll develop the necessary confidence and versatility to grow from standout to star.

“Sometimes Joey’s struggled knowing what type of persona to project onstage,” says ballet master Clinton Luckett. “Lensky showed a dramatic possession and expressive range in him we hadn’t seen before. He’s still very young, but there are a lot of possibilities, which is one of the thrills of working with him.”

A Lesson in Patience

Born in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Gorak fell in love with ballet at age 4, when his parents took him to see The Nutcracker. His family moved to Texas soon after, where he enrolled at the North Central School of Ballet outside of Dallas. At 14, he attended the Orlando Ballet School’s summer intensive, where then-director Peter Stark offered him a scholarship to attend year-round. Rather than ship the young teenager off to Florida alone, his family moved with him.

“It was crazy,” he recalls. “We had two weeks’ notice before the start of classes, so my dad moved with me while my mother and brother stayed behind to sell the house.” His father, who works for AT&T, was able to transfer, while his mother took an open receptionist position at the ballet school. There, Gorak received one-on-one coaching from Stark and the late Fernando Bujones, who at the time was Orlando Ballet’s artistic director. “Working with Fernando taught me a lot about precision,” Gorak says. “He and Peter really cleaned up my technique.”

After OBS’s year-end showcase, Bujones offered the 15-year-old a company position with the understanding that he continue training with the school at night and finish academics via correspondence. But that November, just as Gorak was beginning his professional career, Bujones died of cancer. “We were devastated,” Gorak says.

While in Orlando, Gorak started training for international competitions. “I am not a competition dancer at all,” he says, laughing. “I put too much pressure on myself. I wouldn’t watch anyone else—I’d go in, do my variation and leave the building.” Nevertheless, he won medals at the 2005 Youth America Grand Prix and Helsinki International Ballet Competition. The following year he was awarded the YAGP Grand Prix—and a spot with ABT II. It was a special moment for Gorak, who’d long dreamed of dancing with ABT.

The second company offered him a safe haven in which to grow. But after two years, Gorak still hadn’t received a full-company contract. “It was hard,” he says. “The people I had started with had already gotten into the company.” He was offered the option to stay on a third year. Discouraged, he auditioned elsewhere but ultimately grew determined to stick it out. “I thought, ‘I’ve made it this far. Let’s see if I can really do this.’ ” His patience paid off: Six months later, in January 2009, he was promoted into the company.

Gorak in “Swan Lake.” Photo by Gene Schiavone, Courtesy ABT.

Gorak in “Swan Lake.” Photo by Gene Schiavone, Courtesy ABT.

“Always Questioning, Always Pushing”

Gorak’s first major opportunity came in 2011, when artistic director Kevin McKenzie selected him and corps member Christine Shevchenko to represent ABT at the Erik Bruhn Prize competition. “Joey is incredibly gifted,” says McKenzie. “I chose him because I wanted him to start fleshing out the things he needs more experience with—partnering and dynamic dimension in his dancing.”

Gorak’s previous competition jitters had alleviated with time, but he felt pressure to represent the company well. While he was preparing, Hallberg took him under his wing, helping him with rehearsals and lending moral support. “David told me to see this as an opportunity to work one-on-one with Kevin, that it’s not about winning or losing,” says Gorak. “It’s the process, the road getting there.”

The advice worked: After he and Shevchenko performed the La Sylphide pas de deux and a contemporary piece choreographed by company dancer Nicola Curry, Gorak was announced the winner. Dumbfounded, he had to be nudged forward by McKenzie and Curry to accept his prize. “It didn’t hit me—I wasn’t expecting them to call my name!”

“A lot of times dancers with high potential don’t know how good they are,” says Hallberg, who sees similarities in their physique and temperament. “He’s always questioning, always doubting, always pushing himself. It’s a matter of empowering him, giving him the confidence he needs to push his ability farther.” Hallberg has continued to be a mentor to Gorak. “David reassures me of why I’m here,” Gorak says.

After the competition, roles started coming: the Nutcracker Prince, a lead in Alexei Ratmansky’s Dumbarton, the principal role in Demis Volpi’s Private Light. This summer he made his debut as a buttery-smooth Bluebird in The Sleeping Beauty. But his portrayal of the doomed Lensky is particularly notable. “Everything Lensky does comes from the heart. That’s why he reacts the way he does when Onegin is dancing with Olga,” says Gorak, who spent hours in ABT’s video room, researching his character. “I try to immerse myself in the story onstage. He’s an honest character, so I need to dance him honestly.”

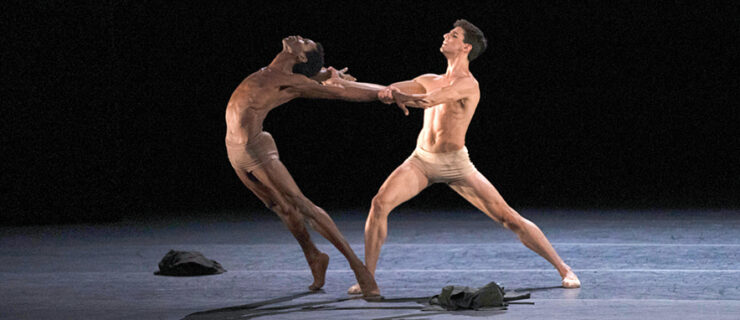

Yuriko Kajiya and Gorak in “Onegin.” Photo by MIRA.

Yuriko Kajiya and Gorak in “Onegin.” Photo by MIRA.

Simplicity Over Flash

Gorak’s lithe physique and sensitive temperament lend themselves to more elegant roles. “I’ve always wanted to be princely and handsome,” he says, citing Siegfried and Albrecht as dream roles. He prefers simplicity to flash, and feels many of today’s male dancers are overly focused on perfecting tricks. “In the end it’s not a circus. There’s a time and a place for it, but not in white tights.”

After a day’s work, Gorak makes an effort to leave the studio behind him. “I completely separate ballet from the real world,” he says. In the off-season he flies home to Orlando to visit his parents and brother, who has special needs. Someday, he hopes to incorporate his love for animals into a post-dance career. “I’d love to work in animal cruelty prevention,” he says.

Luckett and Hallberg both note that Gorak’s biggest test going forward will be his willingness to push his boundaries. “Gifted dancers tend to go to their comfort zone and rely on their strengths,” says Luckett. “I hope Joseph can continue to grow and round himself out as an artist.”

While the current flurry of opportunity might have made a younger Gorak buckle, today he feels more self-assured: “It’s not overwhelming me. I’m at an age and a point in my career where I’m ready to do more.” Does he think a promotion to soloist is in the future? “I try not to dwell on that,” he says. “Each day is a new experience. It’s what I make of it.”

Hallberg agrees: “When you have the desire and the hunger like he does, it’s important to take things into your own hands—and I see that happening.”