"We Are Moving Forward": Debra Austin on Balanchine, Nureyev, and Ballet's Diversity Issues

Debra Austin has a special place in dance history: In 1971, at age 16, she was the first African American woman George Balanchine hired into New York City Ballet. After nine years with the company and two years with Zurich Ballet, she joined Pennsylvania Ballet as a principal dancer, making her the first female African American principal hired by a major U.S. ballet company outside of Dance Theatre of Harlem. Famous for her buoyant jump, Austin’s vast repertoire ranged from classical roles to Balanchine to Hans Van Manen. Since 1997, she’s been passing on her knowledge as ballet master at Carolina Ballet, a company led by her former director at PAB, Robert “Ricky” Weiss.

In honor of her achievements, Texas Christian University’s School of Classical and Contemporary Dance has named Austin as this year’s Cecil H. and Ida Green Honors Chair. She started at TCU this week, where she’s been leading master classes and cross-department collaborations, attending cultural events and giving lectures. We caught up with Austin prior to her residency to talk about her extraordinary career.

Where did you first start ballet?

I first studied ballet at a local school down the street, in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. The woman there told me I had no talent, so my parents said forget that. Luckily, a school called Children’s Ballet Theatre in Carnegie Hall had an offshoot school in Riverdale. My teacher there was a former New York City Ballet soloist named Barbara Walczack—she was in the original cast of Agon.

When I was 11, Barbara contacted Diana Adams, then the director of School of American Ballet, and said, “I have a young girl I want you to see.” She wanted me to have more training in a bigger atmosphere. Diana came and watched class and told Barbara she’d take me into the school the following year. At 12, I got a full Ford Foundation scholarship to SAB and a half scholarship to Professional Children’s School. Sometimes I look back and think if I had not been given that opportunity, I would not have gotten this far in my career!

Were there other African American students at SAB at the time?

I remember one, in level B class. But that’s about it. When I was 14 years old, the school—I think Diana had retired by this point— told me during my evaluations that I would never get into NYCB because I wouldn’t blend into the corps of Swan Lake. But I didn’t leave—why would I?

Talk about the day you got into the company.

When I was 16, Balanchine came and watched our class. Afterwards he took two of my classmates into the company. Then they called me into the office and told me to have my parents call them. I thought, are they going to tell me to go elsewhere? Because I already had it in my mind that I wasn’t going to get into NYCB. I called my mom at work—at the time it was a dime for a pay phone—and told her to call them. Then she called me back and said, “Debbie, Mr. Balanchine just took you into the New York City Ballet!” You see, they had to ask my parents’ permission because of my age and child labor laws. I was so thrilled!

Did it sink in that you were the first African American woman hired into NYCB?

No, not really. Mr. B didn’t really want it to be publicized. Trust me, there were people who wanted to interview me and he kind of squashed that. I was one of his dancers, period, the end. Just like everybody else.

Were you aware of other black ballerinas during your early career?

No. When I was a child, Arthur Mitchell was who I could look up to and that was about it. I knew of Janet Collins. But at the time I didn’t really know who Raven Wilkinson was. I used to pass her in the hallway of the theater when I was in NYCB and she was in City Opera—I didn’t put it together until later.

Also, the timeframe between when I started at NYCB in 1971 and when Dance Theatre of Harlem was starting up was very close. Arthur wanted me to join. But I was like, “Arthur, I’ve worked all this time, I really want to dance for City Ballet.”

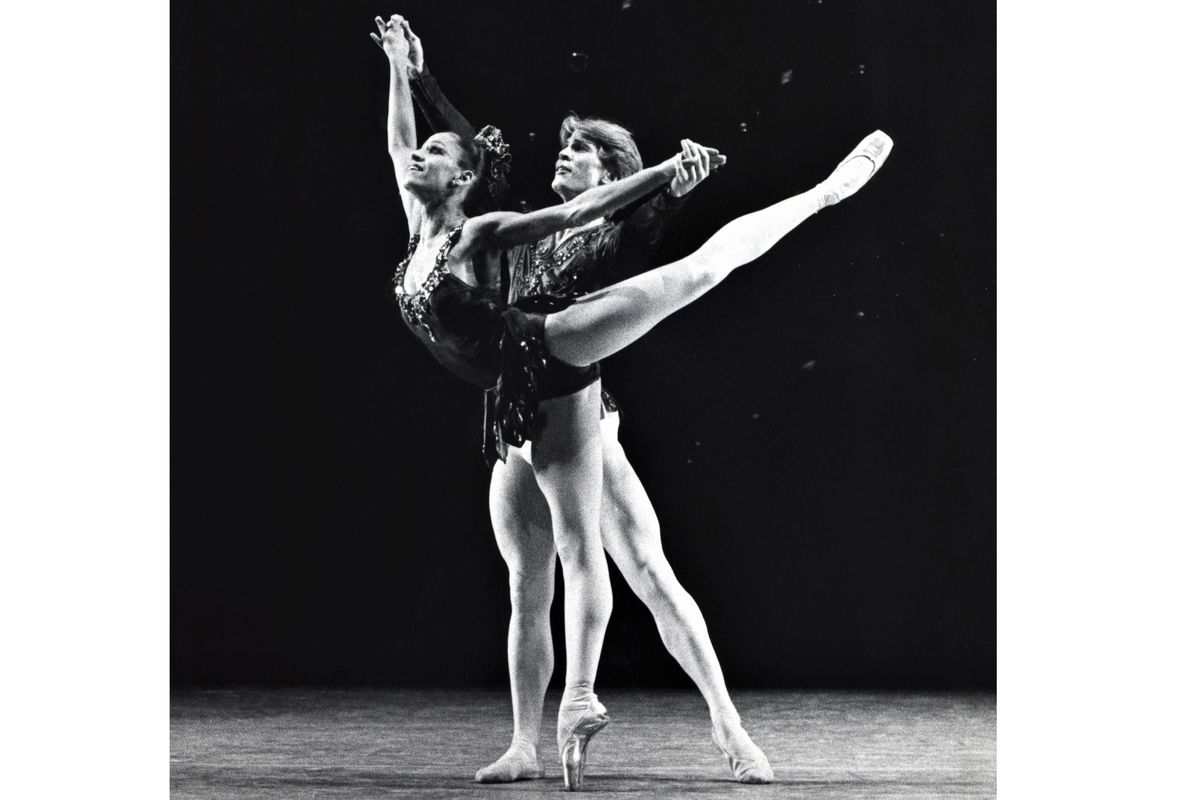

Austin as the “Russian Girl” in Pennsylvania Ballet’s production of Serenade. Copyright Steven Caras, all rights reserved.

What was it like working for Balanchine?

It was quite amazing. Choreography just poured out of him. He was very gentle in rehearsals. He made a solo for me in Ballo Della Regina that always catches my heart. To have been in the studio with him when he created that, the thought that this belongs to me, that this is mine, is so special to me.

What other featured roles did you perform?

John Clifford gave me my very first principal role when I was 19 in his Bartok No. 3. I danced the 3rd Movement principal in Symphony in C, and one of the five soloists in Divertmento No. 15. I danced Fall in Jerome Robbins Four Seasons, and the pas de deux in his Interplay. And for the 1975 Ravel Festival Jerry choreographed a ballet for me, Patricia McBride, Helgi Tomasson and Hermes Conde called Chansons Medecasses, which is now lost.

After nine years, why did you leave NYCB to join Zurich Ballet?

I just felt like I needed to get away and do something else. One of my best friends was in Zurich Ballet, and I had visited her and loved Switzerland. Also, Balanchine was there a lot—it was a sister company to NYCB, so it didn’t really feel too far from the bird’s nest. But it also gave me the opportunity to work with European choreographers. I did Myrtha in Heinz Spoerli’s Giselle, I danced Hans Van Manen’s works—it gave me another taste of what dancing was like outside my comfort zone.

You also danced with

Rudolf Nureyev while you were there. What was he like?

Yes, our director Pat Neary used to invite him. We did his Manfred, and we all danced with him in it. Later I danced Apollo with him at Pennsylvania Ballet, for a gala—Suzanne Farrell came and danced Terpsichore and I was Calliope. I loved Rudi, he was a character. He could be very difficult and mean to people, but he was always really kind to me. I was a jumper and I could do double tours and double assembles, and in class he used to say, “Debbie, go show those boys how to do it.”

How did you come to join Pennsylvania Ballet?

After two years in Switzerland I got homesick. When I came back, Balanchine was in the hospital and died shortly afterwards. Peter Martins asked if I wanted to rejoin NYCB, but I said no. I’d already danced there, and it was no longer under Balanchine. Peter said he knew someone who was about to get a directorship, and if I was interested he would put us in touch. It was Ricky Weiss at Pennsylvania Ballet. So Ricky called me up and watched me take class and then took me into Pennsylvania Ballet as a principal.

Were you expecting a principal contract?

I don’t know—I didn’t really think about it at the time. But my God, I had so much opportunity there. I did both Giselle and Myrtha, in the same performance series! I did all the classical roles— La Sylphide and Swan Lake and Coppélia. Richard Tanner’s ballets, Lynn Taylor Corbett. And we did so much Balanchine: “Rubies,” Symphony in C (I’ve danced in every movement), Donizetti Variations, Concerto Barocco—really everything!

Over the course of your career, did you ever feel like there were limitations placed on you?

No, not really. The only time I didn’t get to dance a classical role was after Ricky left PAB and we were without a director for a while. We were doing John Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet and the person who came in to set it didn’t cast me as Juliet. I don’t know what the reason was, but that was the first time ever that I felt like, “Hmm…”

Ricky told me a few years ago that a stager once questioned casting me as the Sylph in La Sylphide. “I’ve never seen a black Sylph,” he said, to which Ricky responded, “Well, have you ever actually seen a sylph?” I’m glad I didn’t know about that conversation then, because it might have affected my confidence and made the role hard to perform.

Are you encouraged by the increased diversity initiatives in ballet companies now?

Yes, very much. I’m on the diversity committee at SAB, and I’ve taught at DTH and have been part of their mentorship program. And now I’m here in Texas working with TCU. What Misty Copeland has done, which is so wonderful, is bring diversity to the forefront at ballet companies, because dancers have been rejected because they were black, or Asian—it’s a fact. And it has also given black dancers from past generations a place in history. When you think about it, I was at NYCB by myself for nine years—there was no other black dancer until I left. So we are moving forward.