Backstage Notes: Conversations With Carla Fracci

Last month, the legendary Italian ballerina Carla Fracci passed away at the age of 84. A star whose name was eponymous for La Scala Ballet in Milan, she went on to have an international career with companies including The Royal Ballet and American Ballet Theatre. Over her five-decade career she developed partnerships with the greatest male stars of the age, including Rudolf Nureyev and Erik Bruhn. She also acted on television and in films, playing Tamara Karsavina in the 1980 movie Nijinsky, and would go on to direct ballet companies in Naples, Verona and Rome. Often called the “Duse of the dance” (referencing the great Italian actress Eleanora Duse), Fracci became famous for her bringing vivid spontaneity and depth to her roles, from her signature Giselle to The Accused (Lizzie Borden) in Agnes DeMille’s Fall River Legend.

In October 2006, I had the pleasure of conducting a series of interviews with Fracci for my book, First Position: A Century of Ballet Artists (ABC-CLIO). After the interviews ended, she and her husband, Beppe Menegatti, graciously invited me to their home. Our conversation was wide-ranging (including our ideal casts of present-day dancers for various ballets, the role of the Alonsos in Cuba), and she shared anecdotes about partnering.

Below are some excerpts from First Position‘s final chapter. I deliberately chose the chapter on Fracci to be the book’s “closer,” as you would choose a particular ballet work to close a program. Her philosophy of sharing her experiences, while leaving space for dancers to shape their own, seemed singularly important to leave the reader with.

Childhood Inspiration

As a mandolin-bearing page in La Scala’s The Sleeping Beauty, Carla Fracci stood along the stairs Aurora walks down. As she put it, “As Aurora, Margot Fonteyn descended straight into this young girl’s heart!” Afterwards, she saw Frederick Ashton correct just one finger on Fonteyn’s hand. Seeing that even someone as beautiful as Fonteyn could invite such a minute correction sparked Fracci’s desire to be seen dancing precisely and carefully, through a teacher’s eye.

“I wanted to be like Margot Fonteyn, to have that light in my eyes. I tried to form myself like her, working with [teachers] Edda Martignoni and Esmée Bulnes.”

Never Take a Role for Granted

Fracci refers to Giselle as her “warhorse,” but returns again and again to a single idea: “Never take a ballet for granted just because you have danced it many times. No! Look and learn from your [guest] artists. How does she approach the role? What does she bring from her culture? Notice and observe that, ‘Ah, this one is Russian, very strong technically and beautiful.’ There are so many approaches to learn from.”

Studio Versus Stage

“Technique belongs there onstage, but don’t show it as you would in the studio. Show what is behind that développé à la seconde. Show that ‘This arabesque is floating because she doesn’t really touch the ground.’ The reading you decide on determines the kind of coordination of arms and legs, what is inside the port de bras and you! Each dancer arrives at a point where they make it their own. It’s not nice to tell someone, ‘I did it this way,’ because it has to be theirs—even the counts. It’s the transmission, a trasmettere, the tradition from [Carlotta] Grisi to today. We are taking care of something precious, like a diamond that gives off a certain light, keeping what we were taught. Legs must both gain and lose technique to achieve the line and feeling.”

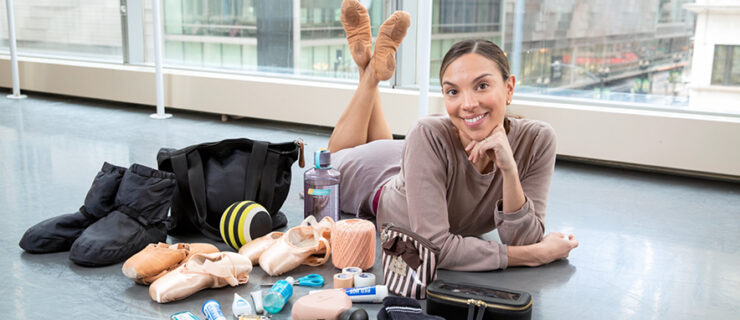

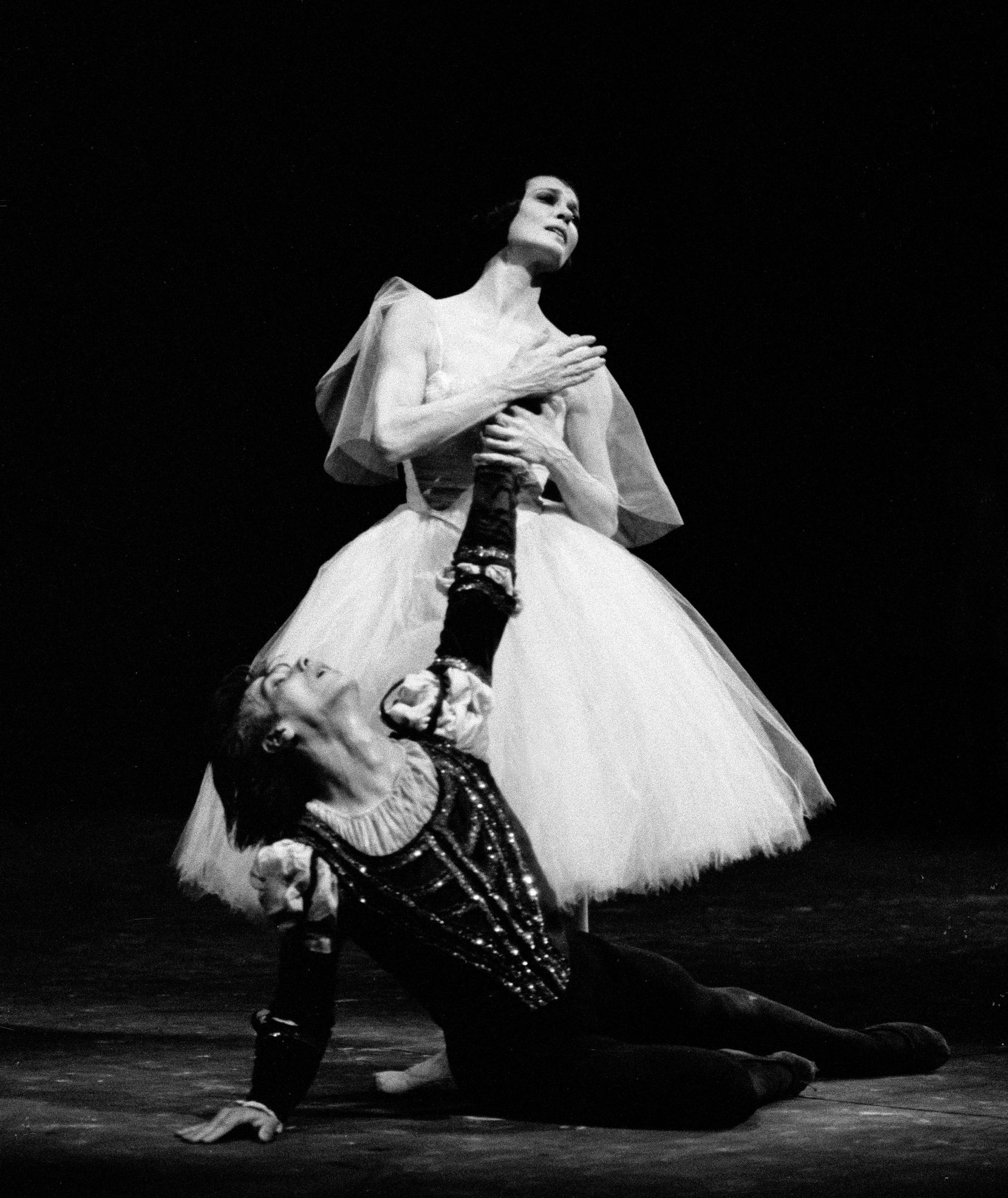

With Gheorghe Iancu in Giselle

With Gheorghe Iancu in Giselle

Lelli Masotti, Courtesy La Scala

Listen and Respond

“Listen to the music as if for the first time to let it inspire you. Look in your partner’s eyes each time, because you will respond differently than the night before. Erik, Rudy and [Vladimir] Vasiliev, from different cultures, worked with different concepts. Value and respond to what they each have, bring, and leave behind.”

The Secret Lies in the Work

“It’s not easy when you are young and hear that you have a beautiful face or costume. Work to show that you are also strong. That is where the teacher is so important in developing an eye that sees what to fix on and offstage the next day: the spine, the legs, the feet. Never rest because you have achieved a certain rank! You will never attain perfection, but taking class keeps you from losing ground. Working daily, and interacting with people who have richness, give you the concept of the role: Read the play if you dance Romeo and Juliet. How else will you understand what is happening between Romeo, the father and Tybalt? Read it! You don’t have words, so informed gestures let you speak with your body.”

Invest Each Beat With Life and Meaning

Relating a story about her friend Alicia Alonso, she notes Alonso’s blindness. When Fracci danced La Sylphide at a Paris gala, Alonso sat in the balcony. Afterwards, she complimented Fracci, “I couldn’t see you, but I saw your wrist, only your wrist!” Her use of the wrist was exquisite and made even the blind Alonso able to “see” the character. The point, Fracci explains, is that every onstage element assumes meaning. The light in Fonteyn’s eyes that made her even more beautiful; where [Alicia] Markova might not have been a beauty, her lightness conferred it, making her work fascinating. In Fracci’s first full-length as Cinderella, she danced with a broom—was “shy with it, then more daring, seeing it as a living person to make it work. Even a broom must be invested with life and meaning.”

“That Dress”

She dives deeper, commenting on [Antony] Tudor’s Juliet. “I had a difficult pas de deux. There were so many characters onstage, all intent on making Juliet marry Paris, someone she didn’t love. They came with the white dress that I would wear at my wedding, and I saw right then that to put on that dress would spell my death. Marrying a man I didn’t love! Suddenly I was in tears. Tudor liked that moment. ‘That dress!’ Beppe heard Tudor say. The dress was the tragedy of this girl. If you feel that, then the music is a part of it. There is no secret. It’s just you, the approach you take, the decision to do new roles to discover who you are in them. Without them, you won’t find the suffering that you don’t know you are capable of to learn about that part of yourself you don’t know, and that every life is not the same. I worked to involve everyone on the stage, to bring everyone with me. By the reaction of the corps de ballet, you know whether you’ve succeeded.”

Erio Piccagliani, Courtesy La Scala Ballet

On Partners, and Sacrifice or Sacrament

Beppe, who is charming, well-read, imaginative, interested in activism, and generous, invited me to join Carla and him for dinner at their Rome apartment built into a ruin overlooking the Colosseum. Also present were Carla’s niece and aide, Barbara Gronchi, and ballet mistress Gillian Wittingham. Carla says of Rudolf Nureyev, “My God, he was so rough with me!” “How so?” we ask in unison. “He…” she hesitates, searching for an English word. Frustrated, she finally says, “He bruscatami, dragged me between his legs!” We are all puzzled by the verb “bruscare.” Beppe leaves the table, returning with a massive Italian-English dictionary. “Bruscare” is “to scrape a wooden ship’s hull.” We collapse in laughter at the visual of Rudy handling Carla so brutishly, aware that she harbors more sanguine memories of Nureyev’s generosity and kindliness.

We speak again of Erik Bruhn and the irony that ballet partners often share a lifelong mutual love that is non pareil. It’s an evening that promises to be unforgettable. You consider that if you overstay, there will be a surfeit of delightful details to recollect. Beppe asks about revolutionary activism. “Does it require too much sacrifice?” Earlier, Fracci has raised and dismissed the same question about the life of a dancer. Both pursuits aspire to leave the world a better place. Carla and I exchange glances, smile and agree that doing so falls more into the category of a sacrament than a sacrifice, especially if one’s commitment and discipline are at the service of bringing and transmitting the best that humankind can create for generations to come.