New Book The Swans of Harlem Spotlights 5 Pioneering DTH Ballerinas

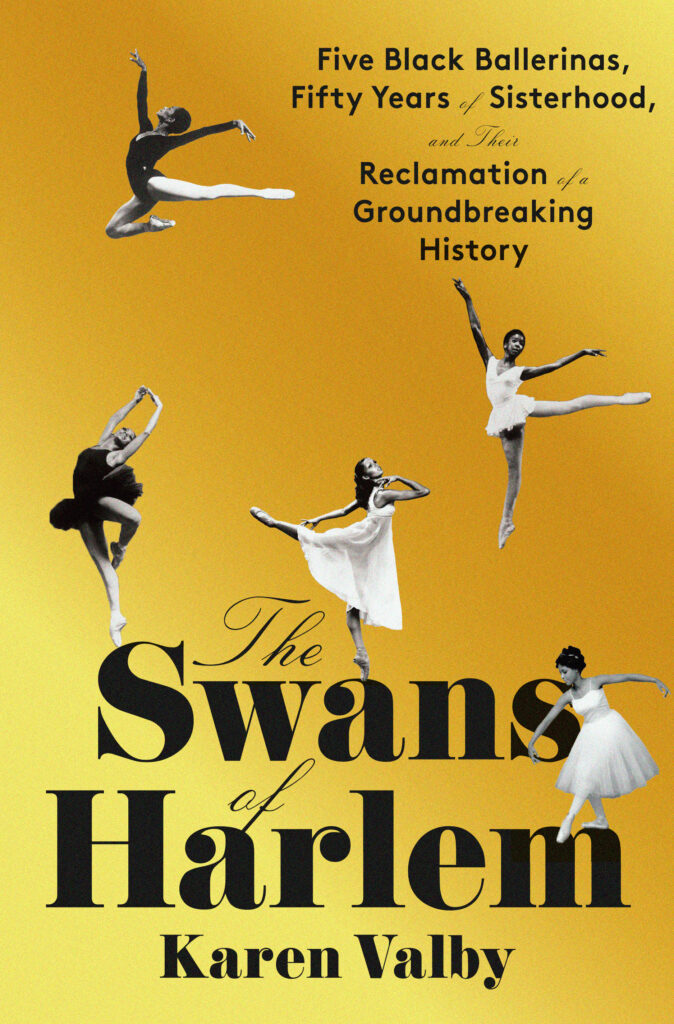

Ballet-book lovers are in for a treat this spring with the release of Karen Valby’s The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History (Penguin Random House, $29). Valby’s book, out April 30, reports on five women who were the bedrock of Arthur Mitchell’s Dance Theatre of Harlem. Lydia Abarca Mitchell was a prima ballerina for the troupe, and the first Black ballerina to grace the cover of Dance Magazine. Gayle McKinney-Griffith and Sheila Rohan were founding company members, as well, while Karlya Shelton and Marcia Sells were among DTH’s “first generation” of dancers. Each of these women has a unique and important story to tell about their ballet careers, working with Arthur Mitchell, and their contributions to launching this company on the world stage.

Pointe caught up with Abarca Mitchell and Valby by email to talk about The Swans of Harlem and about life in the early days of DTH.

Tell us about the genesis of this book.

Karen Valby: One of the Swans—Marcia Sells—is friends with Barbara Jones, a literary agent I’ve known for years. Marcia told Barbara about how she and four other former DTH ballerinas had started the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy to reclaim their role in dance history. Barbara was moved by their ballet careers, but more so by their joining together to insist their lives mattered. It was they who helped break the glass ceiling so that icons like Misty Copeland could soar.

Barbara knew how much a Black dance studio means to my family. I’m the adoptive mother of two Black girls who have danced since they could walk at Ballet Afrique in Austin, Texas. When I pancaked their little shoes before recitals to match their skin color, little did I know it was DTH ballerinas who started that ritual in the 1970s.

The Swans and I met on Zoom in 2020. None of us expected that that first meeting would lead us down a road so grand.

Talk about Arthur Mitchell’s role in birthing DTH.

KV: Arthur Mitchell was one of the greatest classical danseurs, and the first principal Black dancer in Balanchine’s New York City Ballet. With Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1968 assassination, Mitchell felt called to be a changemaker in his broken country. Through vision and force of will, he built DTH out of a little church basement in his childhood neighborhood. Black dancers, with varying degrees of training, flocked. He molded them into a beloved, critically acclaimed company that proved how much more vital, beautiful, and exciting the art form could be with them in it.

Lydia, what was it like to work with him?

Lydia Abarca Mitchell: We were young, some of us teenagers. We were eager to work together and eager to please. It was clear we wouldn’t be coddled, lied to, or indulged. We were on a mission as pioneers and ambassadors. It wasn’t only to prove we could do ballet—we could—it was to present a sophisticated, talented, world-class company of color to a world that thought the only people who should dance ballet were already doing it. Mitchell was dynamic, brutally honest, and driven to make us accomplish what he envisioned for young dancers of color everywhere [through] opportunity and the pursuit of excellence.

What is your advice for today’s aspiring Black ballerinas?

LAM: Work hard, listen, apply corrections, and don’t give up. Show initiative. Learn more challenging choreography. Believe in yourself. Know your worth. Explore companies that will nurture you, not typecast or limit you. DTH broke the glass ceiling in 1969 and is going strong after 55 years! There’s Ballethnic Dance Company in Atlanta, Collage Dance Collective in Memphis, Complexions Contemporary Ballet, Alonzo King LINES Ballet, and more. Participate in summer intensives and look for emerging ballet companies whose personnel represents the modern world of ballet. And, have a plan B. Injuries, illnesses, or other career-ending events can’t always be avoided.

Karen, what are the plans to bring these amazing women to the public?

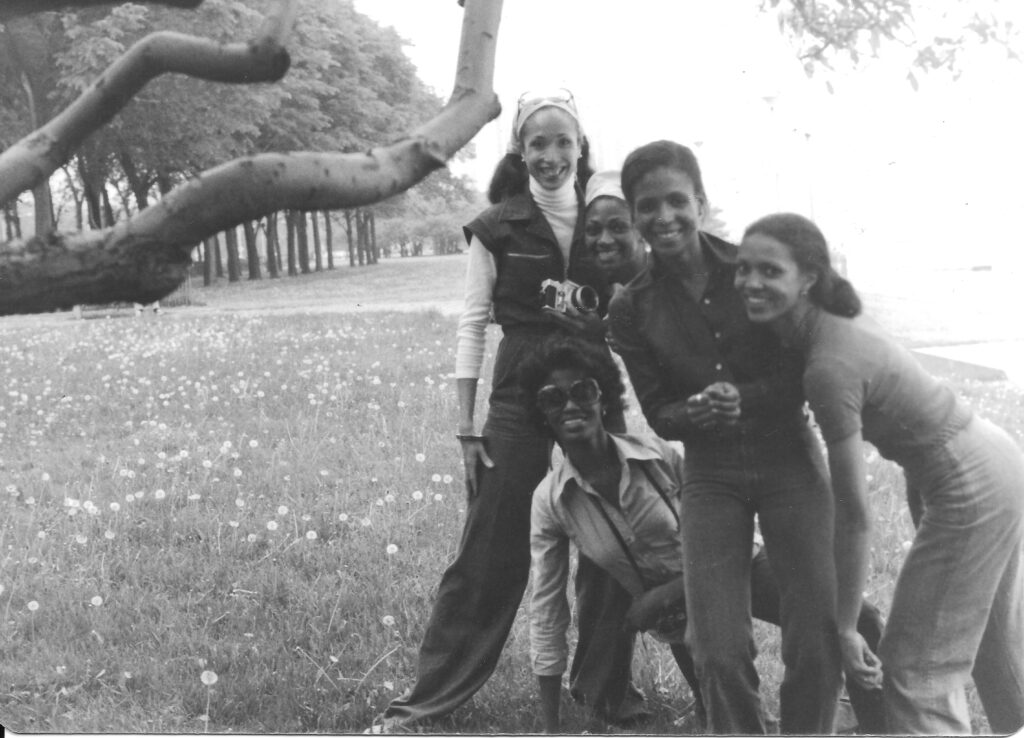

KV: We are hitting the road on a book tour! What’s most moving is getting ready in a hotel room before and laughing in the car at the end of the night. Half a century ago these women were doing this exact thing—harnessing nerves before showtime, entering a space with one another, releasing adrenaline by laughing the bus back to the hotel. To be with these women is a gift.

I hope the book will expand our vision of who ballet belongs to and who’s made it great. I hope any reader who thinks “Wow, I had no idea…” considers why that might be, and who else’s histories are missing from our history. I want also to call out the power of sisterhood. As girls, the Swans quested doggedly for perfection. As grown women, they had to make sense of their lives offstage, where we are all imperfect. They helped each other make peace with their time onstage and in Arthur Mitchell’s studio, as well as in the lives they built after.

Can you call out some dance books for us?

KV: First, the years of heroic work Theresa Ruth Howard has done as founder and curator of Memoirs of Blacks in Ballet. In addition, (Re:) Claiming Ballet, edited by Adesola Akinleye. Historians like Dr. Brenda Dixon-Gottschild and Dr. Joselli Deans and dance writer Zita Allen are treasures. Finally, Judy Tyrus and Paul Novosel published a wonderful ode to DTH [Dance Theatre of Harlem: A History, A Movement, A Celebration] in 2021.

Lydia, what’s most surprising about your ballet career?

LAM: I studied ballet on full scholarship for six years as a youngster at excellent institutions, four at Juilliard and two at Harkness House for Ballet Arts, but I didn’t know what I was working towards and finally quit. After finishing high school, one of my sisters (I have five) took violin lessons at Harlem School of the Arts and told me a Black guy was “teaching ballet” there. I had never had a Black ballet teacher and figured he could make it more “relatable.” It was Arthur Mitchell, starting a ballet company. He offered me $150 a week to quit my summer job at the bank and come dance for him! He invited me to my first ballet performance at New York City Ballet to see him dance. I fell in love with ballet! Under his mentorship and classes with Karel Shook, this little half-Puerto Rican, half-Black skinny girl from the Grant Houses in Harlem became a star! I got to travel, meet famous celebrities, dance iconic roles, and do a 180 from my very first impression of ballet.